Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

In this post, we will explain what Year 11 Module A: Narratives that Shape Our World is about. We’ll also show you how to address the syllabus rubric for this Module to score Band 6 results. Finally, we’ll explain in detail what the syllabus means when it speaks of context, values, attitudes, narratives, and story.

Narratives that Shape Our World is the second Module of the Year 11 English Advanced Preliminary Course. From the 2018/2019 syllabus for Stage 6, Year 11 has compulsory Modules for all students. This is because the Year 11 Modules are preliminary introductions to the Year 12 English Advanced Modules.

Download the FREE Comparative Essay Template for a clear scaffold of a comparative essay PLUS recommended word counts for each section and annotations of an exemplar essay.

A step-by-step planner to help you write exceptional comparative essays! Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you. "*" indicates required fields

Download your FREE comparative essay planner

Download your FREE comparative essay planner

The Modules set for study for English Advanced are:

You can read an overview of the Year 11 Modules in our Beginner’s Guide to Acing HSC English. The NSW Education Standards Authority (NESA) has mandated that all schools study the same three Modules in Year 11. While all students study the same Modules, there are no prescribed texts, meaning that schools will select their own texts for students to study.

Module A: Narratives that Shape Our World is a contextual study. A contextual study asks you to look at a text’s context in detail as part of your study of the text.

Context, for our purposes, is the circumstances of the historical period and conditions during which a text was composed and its composer lived.

When studying Narratives that Shape Our World, you need to think about the conditions that influenced the composer when they composed the text and how their text reflects the context. If you want to jump straight to an explanation of context, follow this link.

The other focus of Module A: Narratives that shape Our World is the importance of narratives and storytelling to human society.

Storytelling and narratives are important aspects of how humans view themselves as individuals, cultures, and nations. This Module asks you to interrogate how the importance of storytelling is reflected in the texts that they study. If you want to jump straight to an explanation of narrative and story, follow this link.

We’ll come back to these ideas in a little bit after we’ve unpacked the rubric for the Module.

Year 11 is a preliminary study that prepares students for Year 12. The Modules in Year 11 English are all designed to introduce students into the key concepts that are the basis for the HSC year.

Year 11’s Module A: Narratives that Shape Our World is the preparation for the Year 12 Module A: Textual Conversations. Both the Year 11 and Year 12 modules are concerned with how composers are influenced by context and values, and how this shapes meaning in their texts.

The Year 12 course takes the core ideas of the Year 11 course and expands on them by asking students to engage in a comparative study that explores how adaptations of earlier texts are shaped by changes in context, values and attitudes.

We can, therefore, interpret Module A: Narratives that Shape Our World as a stepping stone towards your HSC studies. The better you are able to understand the relationship between text, context and values in Year 11’s Module A, the more prepared you will be for Year 12.

Now, let’s look at the syllabus rubric for Narratives that Shape Our World.

To ace Module A, you must first understand what you are expected to demonstrate. This can be found in the rubric.

In this module, students explore a range of narratives from the past and the contemporary era that illuminate and convey ideas, attitudes and values. They consider the powerful role of stories and storytelling as a feature of narrative in past and present societies, as a way of: connecting people within and across cultures, communities and historical eras; inspiring change or consolidating stability; revealing, affirming or questioning cultural practices; sharing collective or individual experiences; or celebrating aesthetic achievement. Students deepen their understanding of how narrative shapes meaning in a range of modes, media and forms, and how it influences the way that individuals and communities understand and represent themselves.

Students analyse and evaluate one or more print, digital and/or multimodal texts to explore how narratives are shaped by the context and values of composers (authors, poets, playwrights, directors, designers and so on) and responders alike. They may investigate how narratives can be appropriated, reimagined or reconceptualised for new audiences. By using narrative in their own compositions students increase their confidence and enjoyment to express personal and public worlds in creative ways.

Students investigate how an author’s use of textual structures, language and stylistic features are crafted for particular purposes, audiences and effects. They examine conventions of narrative, for example setting, voice, point of view, imagery and characterisation and analyse how these are used to shape meaning. Students also explore how rhetorical devices enhance the power of narrative in other textual forms, including persuasive texts. They further develop and apply the conventions of syntax, spelling, punctuation and grammar for specific purposes and effect.

Students work individually and collaboratively to evaluate and refine their own use of narrative devices to creatively express complex ideas about their world in a variety of modes for a range of purposes and critically evaluate the use of narrative devices by other composers.

Source: Module A Rubric from the NESA website

Was the Module A Rubric easy to understand? Like most students, you would have found it difficult to interpret its meaning .

To help you understand the rubric, we have broken it into 6 statements.

Let’s look at the 6 rubric statements and explain them in detail in clear English. This will help you understand what you need to do for the Module and put that into practice.

“Students explore a range of narratives from the past and the contemporary era that illuminate and convey ideas, attitudes, and values.”

You will need to study a range of texts. These texts will reflect the contexts they were composed in. You will explore the text’s context to find out what society’s values and attitudes were at the time and then compare that to the values and attitudes present in the text.

This is what is meant by a contextual study (we discuss context in detail after we finish looking at the Module).

“[Students] consider the powerful role of stories and storytelling as a feature of narrative in past and present societies, as a way of: connecting people within and across cultures, communities and historical eras; inspiring change or consolidating stability; revealing, affirming or questioning cultural practices; sharing collective or individual experiences; or celebrating aesthetic achievement.”

This syllabus point is a bit more complex as there are quite a few ideas at work. Let’s break it down to explain it:

The first statement, “They consider the powerful role of stories and storytelling as a feature of narrative in past and present societies,” refers to the ubiquity of stories and narratives as central features of human society.

That is to say, as long as we’ve been communicating, we’ve been sharing stories and narratives. You need to consider how your text fits into this tradition. You need to evaluate this concept in relation to the list that follows in the second part of the syllabus point.

The second part of the syllabus point refers to the various purposes of our use of stories and narratives.

Let’s break these statements down one by one:

Narratives and stories allow people from different cultures, communities, and nations see what they have in common.

You need to consider whether the text you are studying facilitates this. Does your text seem to be attempting to bridge differences and unify people and cultures?

Some texts are supportive of the context they are produced in. Other texts are deeply critical of their contexts. You can understand whether a text is trying to challenge the values of its context or support them by investigating how it stands in relation to the values and attitudes of the period.

You need to discuss if a text is trying to support or challenge its context and consider how it is doing this.

Some texts introduce people to different cultural practices and ideas. Sometimes texts can support cultural practices. Equally, texts can be used to criticise cultural practices and behaviours.

You need to determine whether this is occurring in the text you have set for study.

Texts allow individuals to see and experience the lives of others. This is a way of sharing experiences and beliefs. Processes of sharing individual and community experiences are a way of forging connections between groups.

You need to investigate to what extent your text shares individual or collective experiences and offers the opportunity for groups to find connections.

Some texts celebrate art and aesthetic choices. Texts might discuss artists and their works. For example, “On the Medusa of Leonardo Da Vinci in the Florentine Gallery” by Percy Bysshe Shelley is an ekphratic discussion of the poet’s response to Da Vinci’s (lost) painting.

Other texts may be studied or discussed because they are considered to be great or important pieces of literature, such as the works of Shakespeare or Wu Cheng’en.

In your study, you need to see if your text is exploring and retelling an existing work as a form of aesthetic flattery or if it is evaluating another’s work.

Acing Module A: Narratives that Shape our World lays the foundation for Year 12 Module A: Textual Conversations. At Matrix, we provide you with clear and structured lessons, quality resources, and personalised feedback from HSC experts!

Learn more about our Year 11 English Advanced Matrix course now.

“Students deepen their understanding of how narrative shapes meaning in a range of modes, media and forms, and how it influences the way that individuals and communities understand and represent themselves.”

There is a connection between narratives and the communities they come from. An individual’s perception of themselves and their community is shaped by narrative. When an individual comes to tell their story and represents their community they will produce a narrative that celebrates or criticises their community, or both.

We can visualise this relationship:

“They may investigate how narratives can be appropriated, reimagined or reconceptualised for new audiences.”

Most narratives are retellings of older stories and ideas. Many philosophers have argued that there are only a limited number of stories that we retell in numerous different narrative forms.

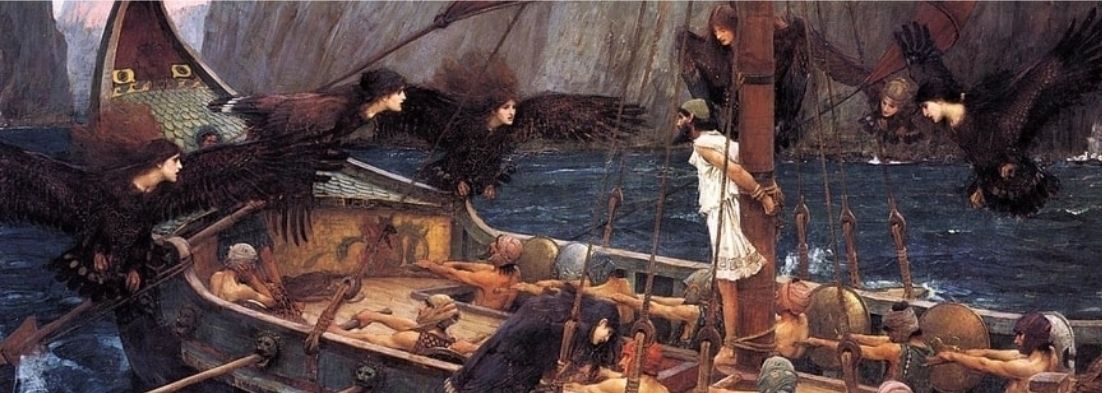

A good example of this is Homer’s Odyssey.

Homer’s Odyssey is the story of Odysseus and his voyage home from the Trojan War. On his way home, he gets blown off course and has many adventures. The story of Odysseus has been retold in many different narratives over time, often these adaptations have new protagonists and characters and are set in completely different contexts.

The following texts are appropriations, reimaginings, or reconceptualisations of Homer’s Odyssey:

This list is by no means exhaustive, but rather illustrates the extent to which powerful stories can be retold as new narratives again and again.

What you need to do when you study Module A, is investigate how your text can and possibly has been retold throughout time. As part of your assessment, you may be asked to produce imaginative recreations of existing texts (a detailed explanation of these tasks and how to approach them can be found here).

The final paragraph of the rubric describes the methodology for analysing texts.

“Students investigate how an author’s use of textual structures, language and stylistic features are crafted for particular purposes, audiences and effects.”

This is telling you to analyse your texts. You must analyse and discuss how composers structure their texts and use various literary, poetic, rhetorical, and/or cinematic techniques to convey meaning.

“They examine conventions of narrative, for example, setting, voice, point of view, imagery and characterization and analyse how these are used to shape meaning.”

This is telling you to research the conventions of narrative and compare them to how your composer has used them in their text. You need to consider how the text has been constructed and how this construction shapes the meaning (that is themes and ideas) we find in the text.

Context can be defined as the circumstances that surround something. To understand this clearly, let’s look at an example.

JK Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter saga, will make an interesting study. Rowling finished the first novel in the series in 1995 and the final novel in the series Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows was finished in 2007.

Let’s look at a couple of examples of how context can influence and be reflected in texts:

Example 1: A composer’s education

Rowling grew up in England in the 1970s. At university, one of the subjects Rowling studied was Medieval literature – including the myths of King Arthur and Merlin. She conceived the idea for Harry Potter while delayed on a train to Manchester. While writing the first manuscript she lived in relative poverty in Edinburgh.

The central narrative of a young boy destined to become a powerful leader is common to both Harry Potter and King Arthur. Arthur pulls a sword from a stone.

This reflects Rowling’s educational context.

Example 2: Contextual events

In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York and the later July 7, 2005 bus attacks in London, many governments, including that of the United Kingdom, introduced increased national security and surveillance programs. Governments such as the United Kingdom began spying on the population and denied such actions even in the face of evidence.

This historical context is reflected in the Harry Potter character, Dolores Umbridge. In The Order of the Phoenix, The Half-Blood Prince, and The Deathly Hallows, government surveillance and media censorship become prominent under Umbridge.

First, Umbridge spies on the students with her cat pictures as headmistress of Hogwarts. Later, in her roles as Senior Undersecretary to the Minister for Magic and Head of the Muggle-Born Registration Commission, she is responsible for censoring the media, spying on citizens and the subsequent denials.

Clearly, this reflects and critiques the context of England in the 2000s.

Context shapes composers’ perceptions of the world and their societies and cultures, and composers comment and critique their contexts through their texts.

When we look at a text’s context, we want to hone in on the values and attitudes of the period.

These are the beliefs held by communities and societies.

Values can encompass religious beliefs, cultural practices, economic and political ideologies, or even fashion choices. For example, democracy is a widely shared value in our contemporary world.

Attitudes are people’s perspectives and views on their society’s values.

Consider how sometimes we support some of our society’s values, but we may also be critical of them.

For example, society expects children to attend school on a regular basis. School children may resent this and feel it a horrible value. These children will have negative attitudes to the value of compulsory school attendance.

Investigating the values of a context allow us to see how a text is commenting on its context. We can see whether a composer is critical of their context within the attitudes they present in their texts.

Now we have an understanding of context, values, and attitudes, we need to consider narratives and stories.

While we often use these words interchangeably, they refer to different things. We need to be clear about these distinctions.

This is the general content of a narrative. It involves the events, characters and settings. For example, the novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J. K. Rowling is a story about a young wizard and his adventures in his first year at the school Hogwarts.

This is both the content of the story and its expression, i.e. the way in which this particular story is told.

For example, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone involves all of the conscious decisions that J.K. Rowling made to give her story about Harry Potter a particular atmosphere, effect, and meaning.

What does this mean, exactly?

Thus, the story of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone can be told and retold by a number of different people in a number of different situations.

However, the narrative we read in the novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone can only be told by J.K. Rowling. In this sense, it belongs to a particular person and a particular time and place in history, i.e. Edinburgh in the early 1990’s.

The difference between story and narratives looks like this:

Can you see how narrative and context are linked, but stories can be timeless?

Stories can be, and are regularly, retold and reshaped into different narratives.

Now you understand what Module A involves, you’re ready to tackle the assessments for this Module.

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.