Change your location

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Has critical reception got you banging your head against the desk? Don't worry, in this post we'll give you the run-down on what it is and how to discuss it.

Join 75,893 students who already have a head start.

"*" indicates required fields

You might also like

Module B in Years 11 and 12 can be pretty full on. Not only do you have to do a rigorous study of your text, you also need to get your head around some complex concepts. While there are already some excellent explanations of textual integrity available, there’s very little information on getting to grips with critical reception, context or significance.

But don’t worry, we’re going to sort that out now.

The Module B syllabus rubric explains how you need to approach the study of your text(s) for the Module.

The Year 11 Module B Rubric states that:

Similarly, the Year 12 Module B Rubric contains the following statements:

So you’re probably wondering what these things mean and how this affects you and your work. Let’s take a look.

At its heart, Module B for both Years 11 and 12 wants you to look at a well-known and respected piece of literature and study it closely to develop a personal perspective on its meaning – what do you think it is about – and whether it is worthy of study.

To do this, you need to think about:

Ultimately, you’re figuring out if the text lives up to its reputation. Is it still relevant to us today? Is it as good as they say? Why?

To make this judgement effectively, you’re going to need to consider a few different things:

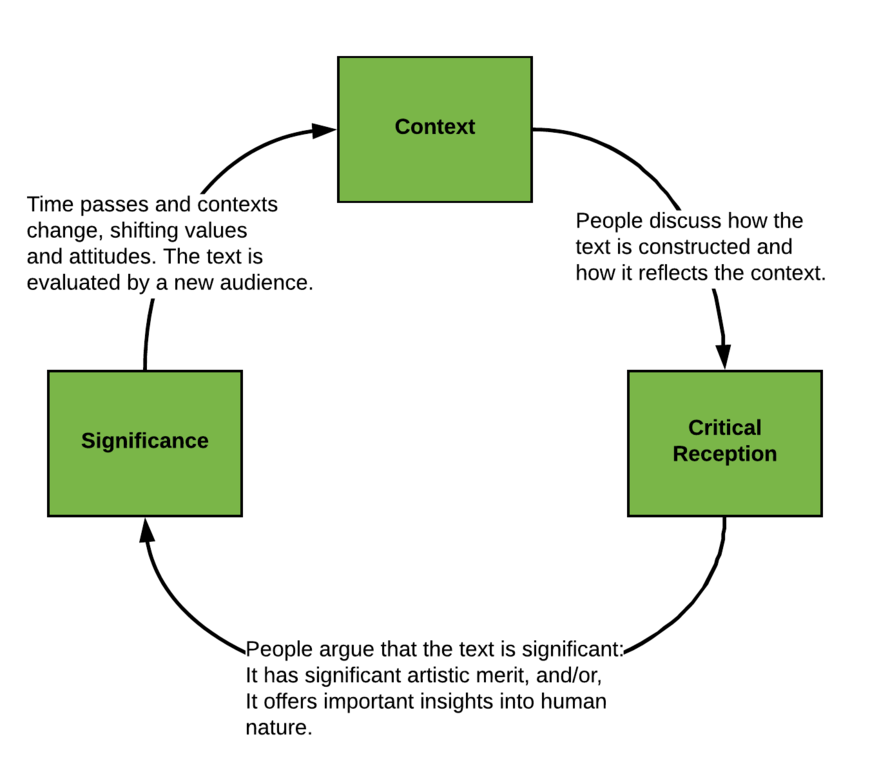

These three concepts are connected, in a way. Let’s take a look at how this relationship works:

Think about this relationship for a moment.

When you read a text for Module B, you are taking part in the reassessment of a text in a new context. This means that you need to reflect on the previous cycles of reception that have occurred previously.

Let’s take a look at how this works by beginning with a consideration of context.

Context refers to a period of time and everything that is going on during that time. When we talk about a text’s context, we’re usually referring to the conditions surrounding the text’s production. This can include:

These elements of context are important because they shape the values of a time – that is, the beliefs widely held by people during that period – and the attitudes people have towards these values – that is, whether they agree or disagree with these values.

So, when composers produce texts, they are making comments about the values and events of their time: we take this to be the attitudes reflected in a text.

Now, you’re probably wondering why we’re talking about context when this isn’t Module A, right? Well, context has relevance for Module B as we’re assessing a texts values. Context can influence a text’s creation and reception in a couple of different ways:

Matrix helps thousands of students nail their HSC each year. The Matrix+ Year 12 English Advanced Course covers all aspects of the new syllabus in detail.

Get ahead with Matrix+ Online

Expert teachers, detailed feedback and one-to-one help. Learn at your own pace, wherever you are.

Critical reception refers to what critics, as a group or individuals, say about a text. Do they celebrate it or do they criticise it or do they ignore it?

A text can be published or released and then receive scathing criticism. People at the time do not like it. But then, as the context changes, the text is re-appraised and people love it.

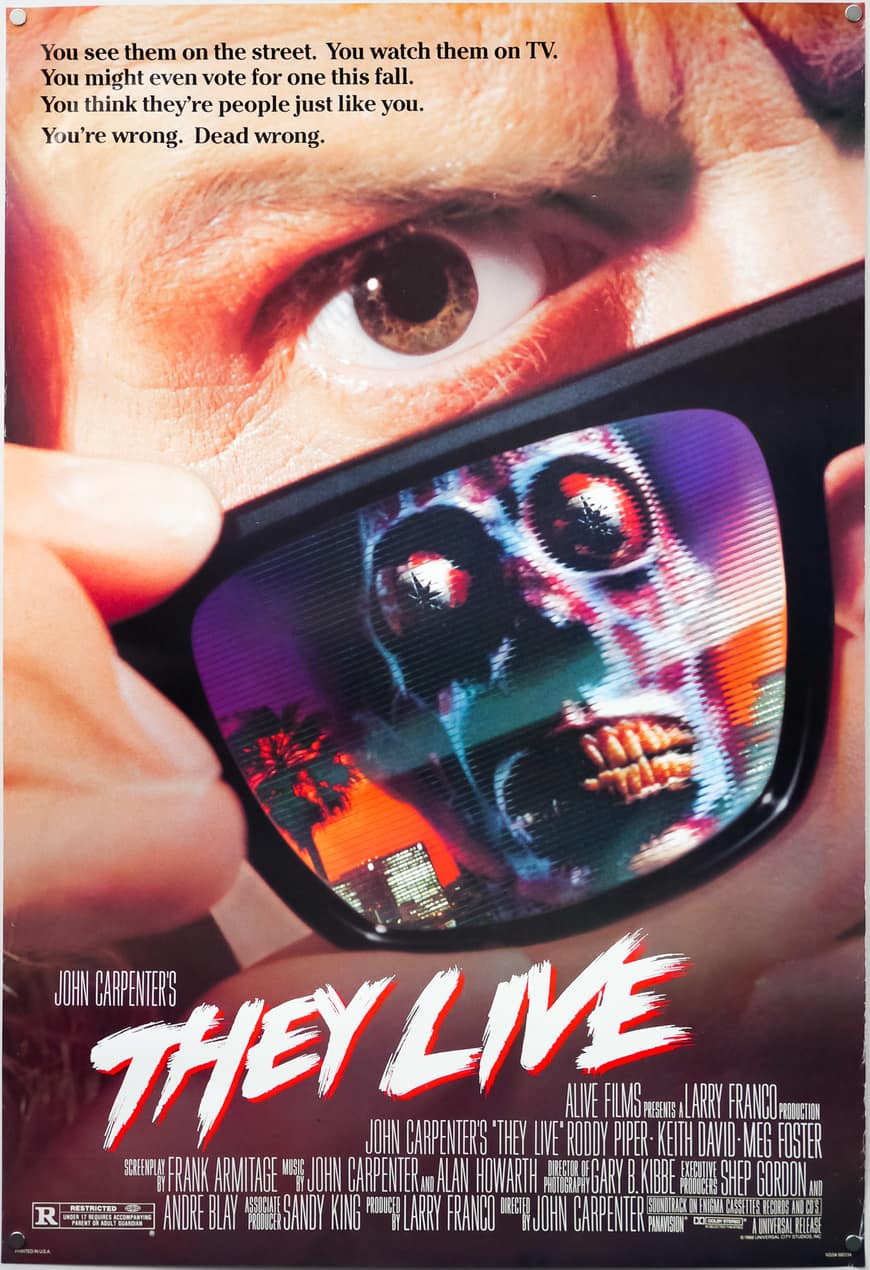

An interesting example of this is John Carpenter’s 1988 Science FIction film, They Live.

At the time of its release, They Live was perceived as a weak B-grade science fiction film. It had a short-lived moment of success at the cinema, but then received poor reviews and performed poorly at the box-office.

Contemporary critics see it differently, many consider it to be an important cult film. Philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek argues that,

“They Live is definitely one of the forgotten masterpieces of the Hollywood Left. … The sunglasses function like a critique of ideology. They allow you to see the real message beneath all the propaganda, glitz, posters and so on. … When you put the sunglasses on you see the dictatorship in democracy, the invisible order which sustains your apparent freedom.”

The example of They Live demonstrates that as contexts change the relevance of a text can change, too. Other examples of texts or composers falling in and out of favour over time include the novels of Charlotte and Emily Bronte, John Donne’s poetry, and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick.

Fluctuations in a text’s reception are common.

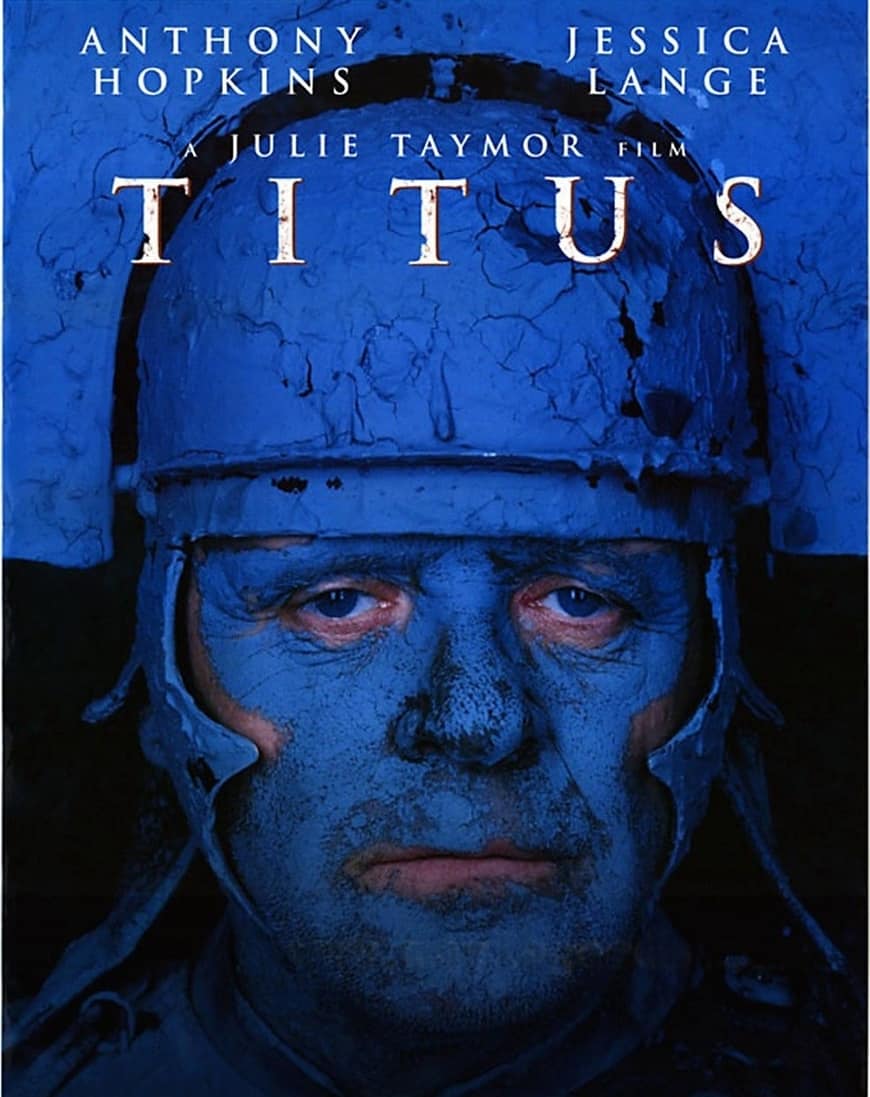

Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus was initially a successful play and was popular in Elizabethan England. But subsequently, its violent content and brutality saw it fall out of favour for centuries. In recent years, though, it has again become popular and been staged by numerous prominent theatre companies around the world.

The texts you have been prescribed to study for Module B have received significant critical praise at some point. Part of your job for this Module is to assess whether that appraisal is justified and whether the text still has a contextual relevance for your context.

To make this assessment effectively you’ll want to consider how the text has been received over time. You’ll need to research the past critical reception of the text and see whether it has had a consistent reception, or if it has been received differently during different periods. Looking at the contexts where the text has fallen in and out of favour will give you clues as to what in the text makes it relevant to particular audiences.

For example, contemporary audiences and critics see Carpenter’s critique of consumerism and oligarchy in They Live as cutting and relevant in a way that those living in the 1980s did not. Similarly, the horrors of Titus Andronicus resonate with contemporary audiences because of events in their context.

Significance means the “quality of being worthy of attention” or something’s “importance.” If we’re discussing a text, we can say that it is significant if:

Significant texts usually share some or all of these qualities.

Let’s look at these ideas in a bit more detail.

A text can be said to be significant if it contains important representations of human existence or experience.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a significant text for many reasons. One of these is its depiction of human emotion and the struggle people have in finding meaning in existence.

The protagonist, Hamlet, Prince of Denmark questions the reason for existence, whether God exists, or whether it is wise to act if we can’t know the truth about our circumstances. These are profound and complex philosophical questions that everybody faces at some point.

Shakespeare makes these issues accessible through his representation of how Hamlet engages with them.

So, even though Hamlet is ultimately a dead white guy, many of the problems he discusses and explores affect people irrespective of colour, context, gender, or class. Hence, the text is significant because of its universal relevance.

Aesthetic considerations such as structure and style can affect how ideas are transmitted. When an artist experiments with form and conveys their message in a new or original manner, it can make a profound impact on audiences.

A good example of artists creating new aestheic conventions are the modernist writers, especially Virginia Woolf.

Virginia Woolf experimented with form because she wanted to convey the complexity of human experience through the medium of the text. Our lived experience is incredibly complex.

In each moment of existence, we experience a wealth of sensory information and emotional responses to these stimuli. In addition, our past experiences and emotions intrude on our present moments and shape our future actions, relationships, and emotional well-being.

Conveying this wealth of information to an audience without overwhelming them or confusing them is a difficult task. Woolf used unique literary structures and techniques to convey this experience in her work.

For example, in To The Lighthouse during the first and final sections, The Window and The Lighthouse, Woolf presents the Ramsay family and the young artist Lilly Briscoe navigating the complexity of interpersonal relationships. Woolf allows the reader to dip into experiences of each character in insightful ways. This distinctly Modernist text explored the interiority of human experience in a rich and unique manner, giving insight into the effects of gender stereotypes and misogyny on individuals.

The second section, Time Passes, was groundbreaking in how it represented the passing of time across a decade and its effect on people and place.

To the Lighthouse is a significant text for several reasons. A significant part of the text’s reputation is attributed to the novel, complex, and insightful aesthetic approaches the Woolf took in constructing her masterpiece.

Some texts are significant because they are important historical or cultural artefacts that reflect a milestone in human development or civilisation. While the subject matter might not have direct contextual audiences, the effect it has on society over a long period of time marks it as significant.

Homer’s Odyssey is a good example of this.

The story of Odysseus’ return to Ithica from Troy contains many thematic elements that aren’t relevant to contemporary Australian society.

The ongoing narrative concern with being a good guest or host doesn’t have the importance in our modern society, where travel is commonplace, relatively easy, and you don’t rely on the kindness and generosity of strangers. Similarly, the representation of female and male roles in society and the expectations of their behaviour do not meet our contemporary community standards.

However, the lasting impact it has had on society throughout the past two and a half millennia mark it as a significant text.

The depiction of Penelope’s behaviour – as the long-suffering and devoted wife waiting loyally for 20 years for her husband to return – was responsible for an unfair and impossible standard for women to follow in European societies.

While Odysseus’ bravery, strength, and cunning defined the ideals of masculinity for many generations of men, the values he embodied are neither particularly healthy or entirely ethical.

So, whether you think the text has had a positive or negative effect on civilisation and society, it is hard to argue that it is not a significant historical artefact.

The short answer for Module B is: you do!

When you study Module B, you are taking the role of the literary critic.

People often struggle to agree on tangible things. Getting them to share a consensus on something subjective such as art is even harder. There is often disagreement over who is allowed to decide the importance of a piece of art for society as a whole.

But this begs the question: What gives one individual the right to say that a text is one that everybody should view?

Much of what we call the classical canon of literature – the texts that are considered must-read – was chosen by a very small demographic – educated, middle to upper-class, European men. What these critics see value in is not going to reflect the values of all society because of the limited experiences of their context.

For example, the values, experiences, and needs of a young woman navigating life in Mumbai are going to very different from the experiences of a middle-class male scholar from Paris or London. These individuals will have quite different ideas about what texts are or are not significant texts.

Most Module B texts come with a significant history of critical praise and reception. Essentially, others have decided that these texts are significant.

This does not mean that they still are.

As a critic, you need to consider the various aspects of context and critical reception we’ve discussed above and decide whether you feel that the text is still relevant and significant for you and your context.

Even if you feel that its themes are not relevant, you need to consider whether the text represents a groundbreaking aesthetic achievement or if it is a historically significant artefact. This means you need to weigh your opinion of the text against the consensus of others and its historical reputation.

These are tough decisions to make. You will need to study your text in detail and engage in substantial research to be able to make an informed and logical judgement on a texts value and significance.

The first step in assessing the value and significance of your text is reading it and reading it multiple times. You then need to analyse it, research it, and discuss it with your friends, family, and teachers.

If you need help starting these steps, you should read the Beginner’s Guide to Acing HSC English. It’s a comprehensive resource that will step you through reading, analysing, and researching a text.

Written by Matrix English Team

The Matrix English Team are tutors and teachers with a passion for English and a dedication to seeing Matrix Students achieving their academic goals.© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.