Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Guide Chapters

Many students are comfortable pulling apart prose, but aren’t sure how to analyse film in Year 9. In this article, we’ll explain why and how you should analyse film to ace your next assessment.

Improve your analysis with templates, study prompts, and essay tips! Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you. "*" indicates required fields

Download your free Film Analysis Planner

Download your free Film Analysis Planner

Films are events captured on camera as a series of moving images that make up a sequence or storyline. You’ve probably encountered films leisurely before, but now we’ll be looking at how we can view films from an analytical perspective.

Fiction is defined as something that is created from the imagination, whereas non-fiction is based on truth or real events.

Establishing the difference between fiction and non-fiction is important to understanding films as they influence why and how a composer (in this case, the filmmaker or director), intended to deliver their message.

Films were traditionally released in movies or theatres, and then accessed through replication on DVDs or streaming channels. Now films are often released straight to online streaming platforms.

Films traditionally have a higher budget and production value and may involve more people in the production of a film in comparison to TV shows (although this is not always the case).

Films mostly are created as stand-alone narratives, although some types of blockbuster films have sequels or are part of a shared universe, think superhero films.

TV shows are made to be broadcast on television or on streaming channels and comprise of any amount of episodes (parts of the overall story) and detail the characters in different situations that relate to an overall plotline. These are released in parts over a period of time.

TV shows can include reality TV, kids programs, dramas, mini-series and more.

Documentaries are a genre of film. Documentaries are non-fiction (factually-based) films that serve more of an informative purpose than entertainment, for example, Sir David Attenborough’s nature documentaries.

Despite their differences, fiction and non-fiction films both have characters and use a range of techniques to develop their meaning. We’ll go into these in depth later in this article.

TV episodes are parts of a greater narrative. They can be analysed like a film but are difficult to understand in isolation as they act as parts of a bigger whole. In this way, we only get a ‘snapshot’ of the broader picture, so more context and background information surrounding the episode needs to be provided.

Like any other text type, films take us on a journey to a world or time other than our own. Not only do they offer a form of escapism or entertainment, but they can encourage us to question the way we see the world and ourselves.

You may have already encountered this with films you have seen that have changed the way you think, act or perceive an idea.

Just like novels, poems and art, films use a variety of techniques to portray ideas and to convey meaning to audiences.

Let’s have a look at how these features apply in film.

Don’t worry! Gain key English skills with our Year 9 English Course.

We can discern a lot of information from the visual elements of a film, so let’s take a look at some of the key aspects of film visualisation.

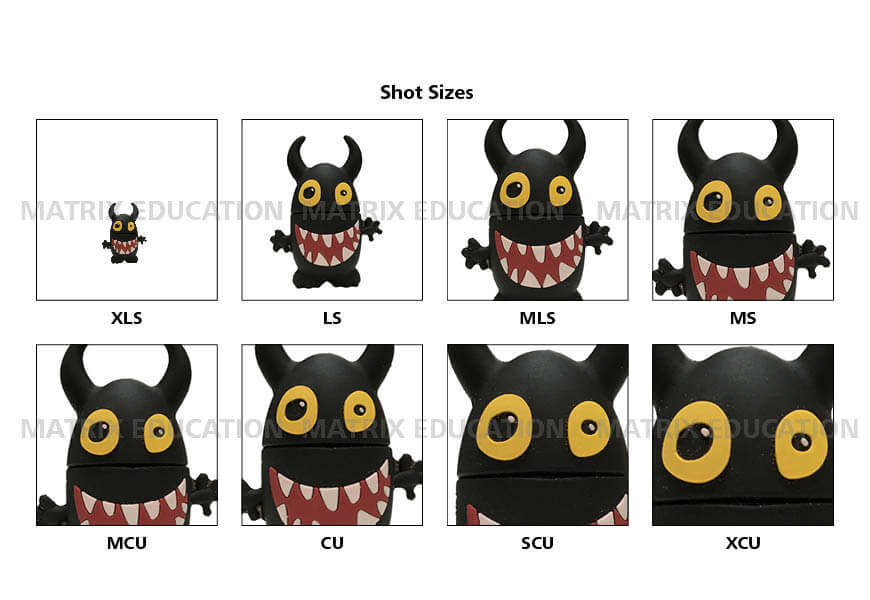

Shots indicate the distance of a camera in relation to the subject or scene. Shot types range from Extreme Long Shot (XLS) where characters are very far away from the camera and appear extremely small, to Extreme Close Up (XCU), where the character is so close to the camera the whole frame is consumed by one part of their face. Consider the examples of shot types:

Note: we’ve provided the shorthand acronyms for these shots which are commonly used in shot lists in film production. Here’s what they look like in relation to a subject:

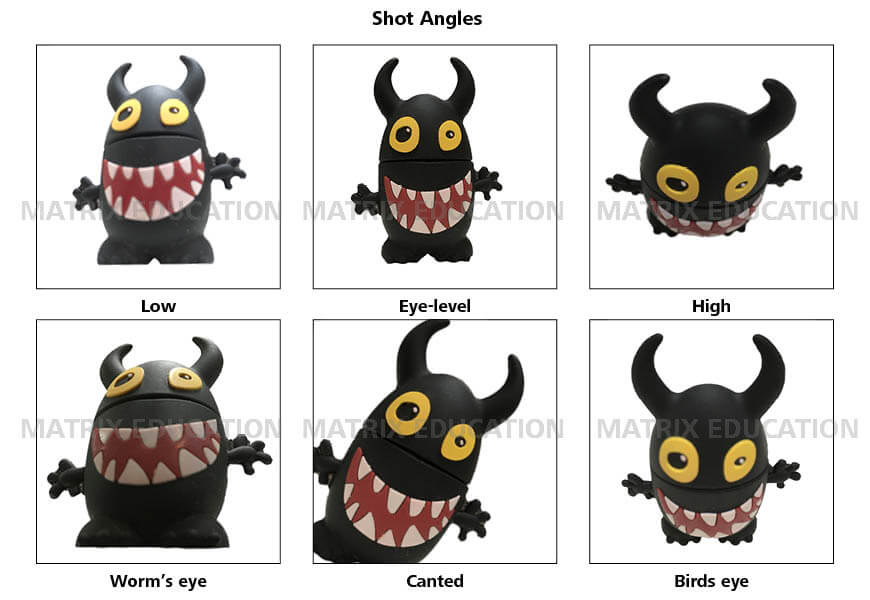

Since shots are measured by the level distance from a camera, angles involve the tilt of a camera in relation to the subject or scene, which affects our point-of-view. Consider these examples of angles, and what they might infer about a subject or scene.

Let’s take a look at shots in action:

The colour pattern or scheme a filmmaker selects is highly important in conveying mood or tone throughout a film. This means we have to consider colours and what emotions are usually associated with them. In film, this goes in more depth through the implementation of hue, saturation and can be enhanced by lighting.

A filmmaker’s deliberate inclusion (or removal) of light is important as it influences the mood of a setting or character. Low lighting reinforces shadows in a shot, which might emphasise the uncertainty of a setting, or the nefarious qualities of a character. Conversely, an overexposed lighting scene may give the shot an ethereal quality.

Composition refers to the elements that make up the shot – so all of the above and more! It’s also referred to as MISE-EN-SCÈNE. When we think about the composition of a shot, we’re taking into account everything that the shot encompasses, from characters, positioning, lighting, props and set.

Along with these visual elements, we need to consider how sound adds meaning to a film. Typically, sound is categorised as either DIEGETIC or NON-DIEGETIC.

Diegetic sound is sound that occurs in the world of the film. This includes background noise, DIALOGUE and sound effects created by characters in the scene.

Non-diegetic sound is sound that occurs outside of the world of the film. This includes MUSIC and NARRATION.

What makes a film a film is the way that visual and aural elements are edited together and combine to form sequences. Here, editing processes are important to consider as filmmakers deliberate on shot duration, cuts, transitions and special effects (SFX) that the film requires once it’s been filmed.

One element of post-production editing involves editing wipes – here are a few examples of these below:

Dialogue is usually studied in isolation from the sound as it contains vital information about the plot, themes, perspective and vision a filmmaker wants to convey. Here are some important elements to consider about dialogue:

Films have been used to tell stories for decades. The power of modern technology has allowed filmmakers to develop more powerful, nuanced and impactful stories than ever before.

Regardless of a film’s genre or style, films are able to tell stories with a combination of aural and visual elements – a skill that was relatively unheard of up until the invention of film. Moreover, films are relatively accessible and easy to consume in comparison to full-length novels.

If you want to learn more about film techniques, check out our Film Techniques Toolkit!

Now that we are across how film operates, let’s work towards analysing a scene from a film.

We will be using a clip from Australian film Rabbit Proof Fence (2002) directed by Phillip Noyce.

Note that even though films usually involve dozens, if not hundreds of production roles, we attribute the overall vision and product of the film to the director.

Before we get started, you need to view the clip. Here it is:

Matrix Education How to Analyse Film in Year 9 Rabbit Proof Fence – Excerpt from Matrix Education on Vimeo.

What does this scene address?

Watch the clip from Rabbit Proof Fence. From a first viewing, the scene depicts an ‘inspection’ of Indigenous Australian children in the outback by white Christian personnel to establish the fairness of Indigenous children.

From this, it can be understood that the film details the forced removal and reintegration of Indigenous Australians into white Australian society, a process known as the Assimilation Policy. This policy produced what’s known as The Stolen Generation – Indigenous Australian children who were taken from their families, made to feel shame for their Indigenous cultures and to incorporate white Australian values in lieu of Indigenous values, cultures and practices.

Themes

Now that we have developed a contextual understanding of the scene, we can argue that the themes that emerge from this scene involve racism, separation, and ‘Othering’ (referring to a person or group of people as ‘the Other’ to separate them from oneself). Take note of these as techniques and mood will contribute to Noyce’s representation of these themes.

Mood

The clip appeared to be void of strong emotions, however, the tense atmosphere created by the reluctance of Molly (the protagonist) and the intensity of Mr Neville are palpable. This affects the mood of the scene, resulting in an uncomfortably rigid mood.

Watch the clip again. Ask yourself, what contributes to the scene’s representation of those themes and the overall MOOD?

Upon reflection, it becomes clear that the

all contribute to the MISE-EN-SCÈNE (composition) of the shot.

The setting in rural Australia with arid conditions situates the chapel and demountable buildings in the desert. The soundscape comprises of loud cicadas (Australian insects) as well as a poorly-sung religious song and dialogue. The colour scheme is highly saturated and the bright lighting contributes to this oversaturation of colour.

What do you think are the effects of Noyce’s decisions in this scene?

Now let’s look shot by shot at the scene, but this time, we can stop, start and replay certain elements of the scene to find out what techniques Noyce has used in this scene:

Now that we’ve identified a few techniques and their effects, we must ask ourselves:

Now that we have a thorough understanding of specific techniques and their effect, what does this technique contribute to the overall meaning of the scene?

What has this scene revealed or suggested as to what might happen next?

Now that you’ve successfully analysed a scene, you can watch the whole film and others in totality.

When you watch a film, think about how a mix of techniques, both visual and auditory, in combination with the editing sequences, have contributed to your understanding of the film altogether. Happy watching!

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.