Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

Select a year to see available courses

Science guides to help you get ahead

Science guides to help you get ahead

Guide Chapters

In the last part of our Guide, we looked at how essays work and discussed the structure and planning of an essay. If you haven’t read it, you should go check that out first. In this part, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of writing the essay and give you some tips for producing Band 6 responses in exam conditions.

But first, we need to discuss what essays are and how they should work.

Write compelling essays for English with clear steps and useful templates. Fill out your details below to get this resource emailed to you. "*" indicates required fields

Free High School English Essay-Writing Guide Download

Free High School English Essay-Writing Guide Download

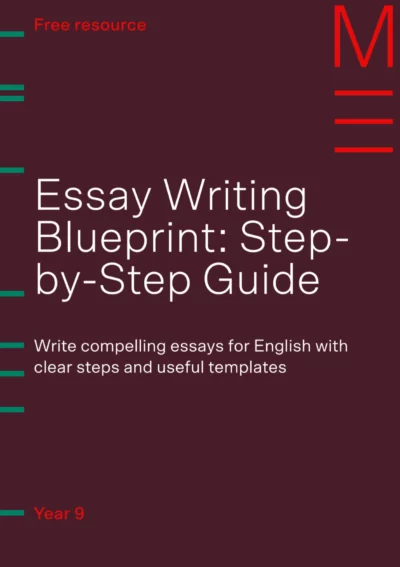

Just to recap this is the process we are using to write an essay:

Now that we’ve refreshed our memory, let’s pick up where we left off with the last post. Let’s put together our body paragraphs.

Now you are ready to start writing. You have your ideas, your thesis, and your examples. So, let’s start putting it together.

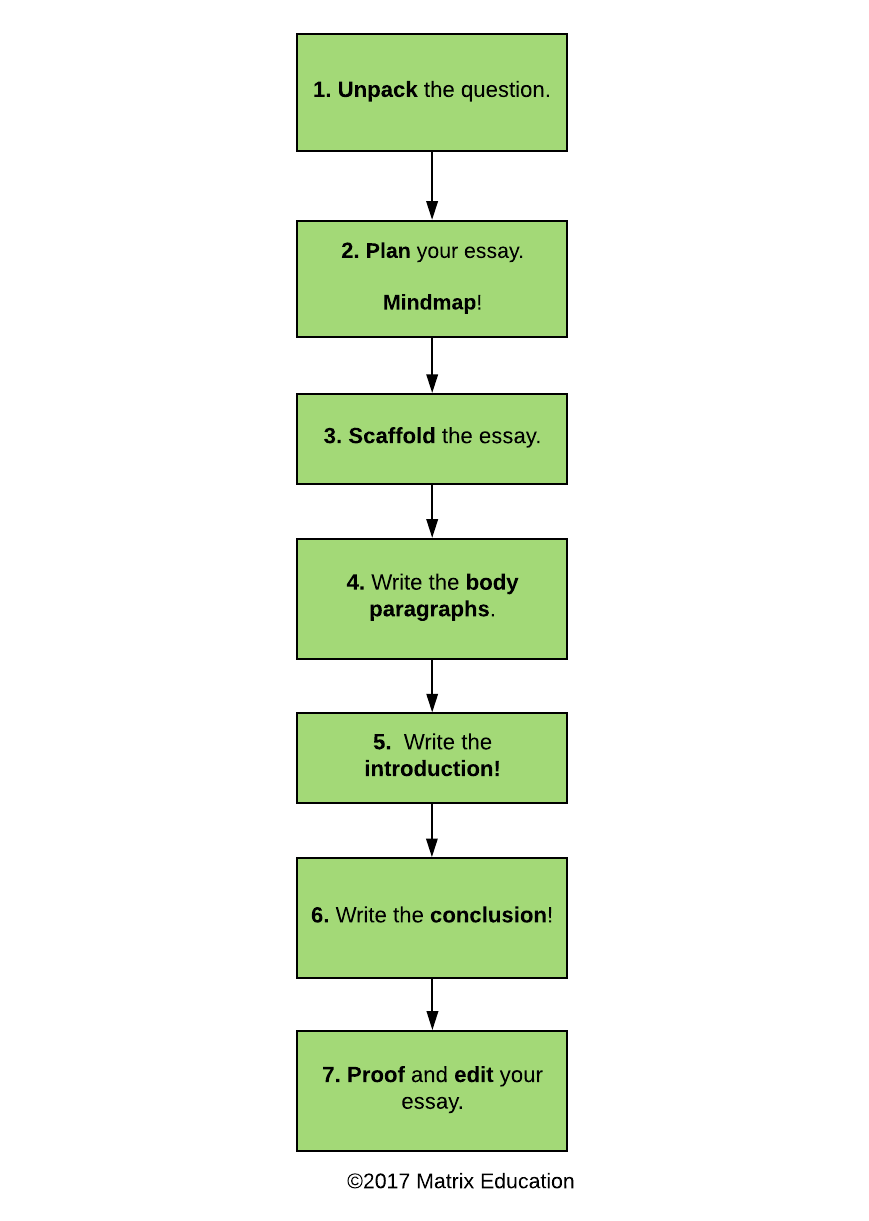

First, let’s think about the structure of a body paragraph. The following diagram visualises the structure of a body paragraph:

A body paragraph has 3 key components:

How do I write a Topic Sentence?

The topic sentence introduces your body paragraph. It must introduce the theme or idea for the paragraph and connect it to the broader argument in the essay. Thus, it is very important that you get it right. This can be daunting, but it shouldn’t be.

So, how do you write a good one? Let’s see:

Now you’ve got your topic sentence, you need to validate it by supporting it with evidence. So, where should you start with this?

In order to demonstrate how to write a body paragraph, let’s consider a student who is writing an essay on Arthur Miller’s The Crucible for Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences. We’ll look at their notes and then a paragraph they’ve produced, before walking you through how to use evidence. Let’s go!

The table below is a sample taken from their notes:

| Table: Study notes for Year 12 Common Module: The Crucible | |||||

Character | Motivation/ Perspective | Example | Technique | Explanation | Connection to Module |

| Abigail | Self-Preservation Power | “If I must answer that, I will leave and I will not come back!” [DANFORTH seems unsteady.] Act 3 | Imperative Tone Stage Direction | Abigail responds to the accusation that she has had an affair with Proctor by refusing to answer Danforth’s question: is this accusation true? Her imperative Tone is important because she is challenging the power of Danforth, the most important and powerful man in Salem. The stage direction indicates that she has power of Danforth. Not only has she protected her self-interest, she has manipulated Danforth. | Miller contrasts the collapse of the community in Salem with the HUAC trials. He focuses on the inversion of power occurring in the court. It is ironic that Abigail, a young girl, has the power to manipulate the Deputy Governor of the Province. Witness collusion with McCarthy led the HUAC trials. She is an example of an individual that had a profound effect on her town and the fledgling United States. She is a pivotal figure in a narrative that shapes how we view partisan politics and pogroms. |

| Proctor | Self-Preservation Power | “You are pulling Heaven down and raising up a whore!” Act 3 | Angry Tone Religious Allusion Metaphor Epithet | Proctor is heartbroken and angry that Elizabeth has been arrested and has lied to protect him. Elizabeth’s lie is tragically ironic: he was relying on her to maintain her integrity to save them all. Proctor blames Abigail for Elizabeth’s arrest and potential execution and those of the other townsfolk. | Miller depicts the corruption of HUAC. Proctor is representative of individuals who fought stood against the trials. It is ironic that Proctor, a predominantly moral man, is bought down by a lie and his adultery. The personal has been unduly politicised similar to how witnesses were convicted for being gay, not merely communist. She is an example of how personal transgressions are persecuted by by society Proctor has since become a symbol of heroism and political martyrdom. |

In their table, the student has broken down their examples by character, themes, technique, effect, and connection to the module. This is important for when students write T.E.E.L paragraphs. This allows them to easily transform their notes into part of an argument. For example, they have all the necessary information ready to incorporate into a T.E.E.L paragraph. Let’s see what that paragraph looks like:

A sample T.E.E.L paragraph |

In The Crucible, Miller represents how Senator McCarthy’s HUAC trials turned citizens against one another. Miller uses the Salem Witch Trials as an historical allegory. In Salem, the young girls who were the cause of the accusations of witchcraft quickly turned on the other townsfolk, inverting the power structure of the town. Similarly, in the HUAC trials witnesses colluding with McCarthy often led the trials and dictated who would be tried and what the charges are. Miller represent this absurd power dynamic with Abigail’s imperative assertion that “If I must answer that, I will leave and I will not come back!” The stage direction “[DANFORTH seems unsteady,]” reveals the power Abigail has over the leading authority in New England. In contrast, Proctor – a moral man – is incriminated by his wife’s desire to protect him by lying. Proctor’s exclamatory metaphor accusing the judges of “pulling Heaven down and raising up a whore!” depicts his righteous anger at the personal being politicised. In The Crucible, Miller is capturing the injustice of an historical event – the HUAC trials where liars and criminals were able to accuse and destroy innocent individuals for being gay, a political and social witch-hunt that became known as the Lavender Scare – if it couldn’t be proven they were communists. |

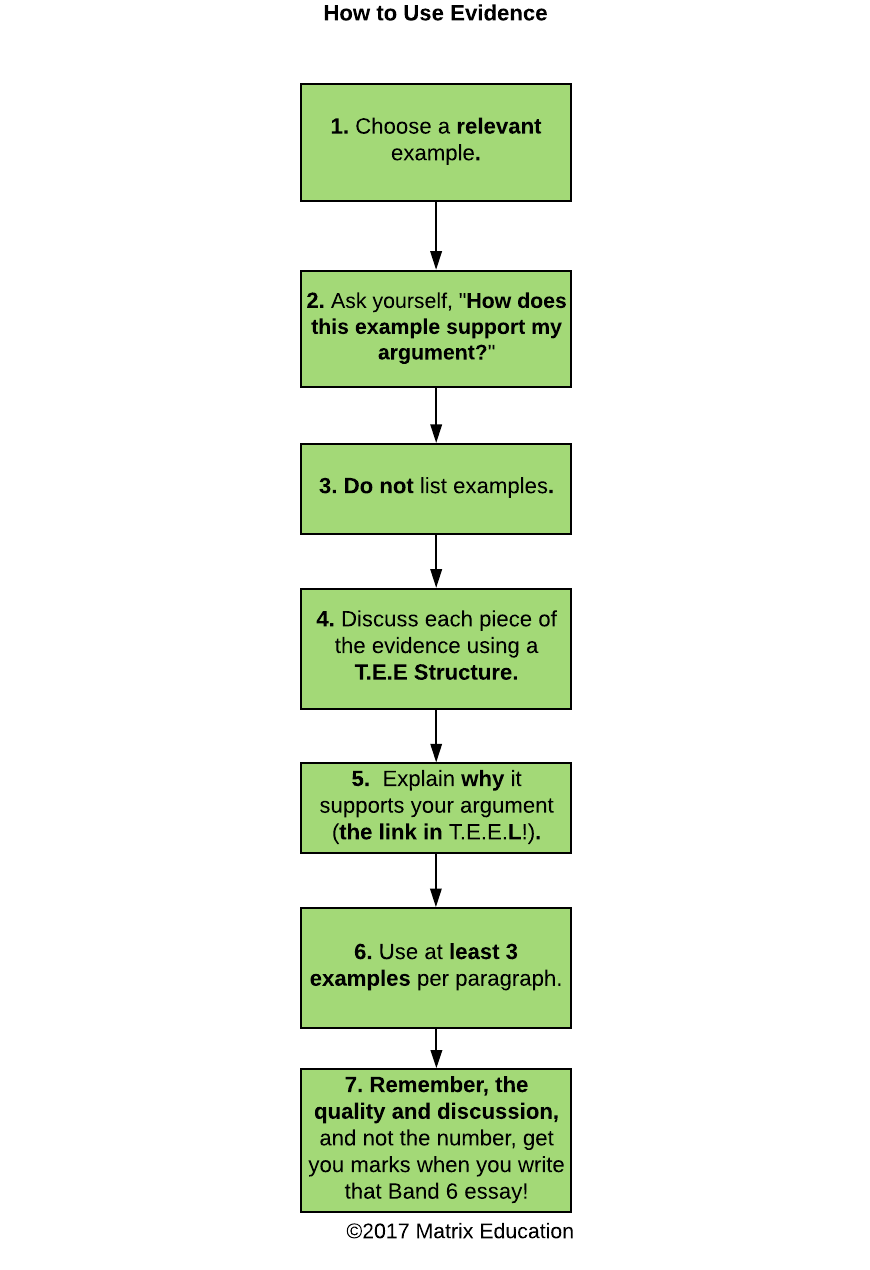

This is a detailed paragraph, so how has the student gone from their notes to a complex response? Let’s see the steps that Matrix English Students are taught to follow when using evidence in a T.E.E.L structure.

Evidence supports your arguments and demonstrates your logic to the reader. This means that your evidence must be relevant to your argument and be explained clearly. Using the following checklist will ensure this:

Now, you’ve got your head around using evidence for the body paragraph, we should quickly discuss addressing the Module and using your supplementary material.

It is not enough to pay lip service to the Module in the introduction and conclusion, you need to discuss it in a sustained manner throughout your response. To do this, you must:

Module B for Year 11s and 12 and Extension English require students to consider the perspectives of others in their writing. Some assessment tasks for other units might require students to read a critical interpretation of their text and discuss it in relation to their own perspective of the text. When doing this, there are some important rules to remember:

Using supplementary material and critical perspectives in essays, especially during exams, is a skill. Matrix students get detailed explanations of how to do this in the Matrix Theory books. The best way to perfect your use of critical perspectives is to write practice essays incorporating them and seeking feedback on your efforts.

If you would like a more detailed explanation of writing body paragraphs, read our posts:

Now that we’ve got our body paragraphs down we need to look at how to write introductions and conclusions.

Introductions and conclusions are very important because they are the first and last words that your marker read. First impressions and final impressions matter, so it is very important to get them right! So, we need to know what an introduction needs to do.

An essay introduction must do a few different things:

Don’t worry, it may sound like a lot, but it isn’t really. Let’s have a look at some of the practical steps that Year 11 Matrix English students learn in class.

A good approach is to break the four purposes of an introduction into a series of questions you should ask yourself:

Initially, it may be easier for you to write your body paragraphs first and then use them to produce your first introduction. This is because:

If you would like more information on writing introductions, you should read our detailed blog posts:

Remember, your conclusion needs to recap your ideas and thesis. You also need to leave a lasting impression on your reader. Conclusion are actually the easiest part of the essay to write.

So, what does writing a conclusion involve? Let’s take a look:

You should only write your conclusion after you have produced the rest of your essay. Often the hardest part is knowing how to finish the conclusion.

The thesis (1.) and thematic framework (2.) need only be reworded from the introduction, but your concluding statement (3.) needs to do something new. The final statement needs to explain the connection of your argument to the module and what YOU have taken away from the study of the module.

It is worthwhile being succinct and honest about your experience of studying the unit, rather than making a hyperbolic statement about human experience (sometimes known as a “pop-outro”). To give you a sense of what this means, consider these Module A concluding statements:

The first statement tells the marker nothing about what the student has taken learned from the module. The statement it makes only partially relates to the module, and it is not original – many students will write something similar.

The second statement gives a personal insight into the student’s experience of reading The Crucible and studying Module A: Narratives that Shaped the World. This second statement is what your markers are looking for!

The best way to get good at writing introductions and conclusions is to practice writing them to a variety of questions. You don’t always have to write the whole essay, but you can (it’s the best practice for writing Band 6 essays)!

If you are still struggling with how to write your conclusion, take the time to read through our detailed blog post Essay Writing Part 5: How to Write a Conclusion.

You can find all of those essay writing blog posts here:

Now that we’ve looked at the basics of how to write an essay, we need to consider the exam essay. It’s one thing to take your time crafting an essay over a couple of hours or days, but an entirely different experience to write one in under 40 minutes. It’s now time to see what that involves and how it differs from the process above.

The most common form of assessment for Stage 6 English is the in-class essay or HSC essay. (You will have to sit at least 6 essays in Year 12!) Let’s have a look at some stratagems for preparing for these assessments.

Markers must assess the following criteria:

It is imperative that you keep these aims in mind at all times when you are writing your essay. Matrix students are taught how to address these criteria in their responses. You must ensure that you demonstrate a skilful ability to answer each of the seven criteria above.

Learn with HSC experts at your convenience to save time and get ahead before your HSC. Learn more!

Start HSC English confidently

Expert teachers, detailed feedback, one-to-one help! Learn from home with Matrix+ Online English courses.

It’s tempting to memorise an essay for an exam. Don’t. It’s a risky strategy and assessors are increasingly asking more complex and specific questions to catch out students who try and game the system like this. This is especially true in the HSC, where the questions are becoming more focused and thematically specific to weed out students who engage in this practice.

Instead, you want to study your texts in a holistic manner that allows you to respond to a wide range of questions. Let’s have a look at some of the tips that Matrix students receive:

This is what to do to prepare, but what do you do during the exam? Let’s see.

Gameday has arrived. You sit in the classroom and wait for your teacher to say: “You may open your paper!” But what do you do after that?

Here is a step-by-step guide:

One of the most difficult parts of dealing with exams is responding to what the questions ask of you. Exams are stressful, and dealing with a potentially unknown quantity can add to the anxiety. But there are some strategies to take the sting out of this. Let’s see what they are:

Let’s have a look at an example question for Module A – Narratives that Shaped the World.

“Storytelling is core to human identity. Individuals test their perceptions of the world against those experienced vicariously through texts.”To what extent do you agree with this statement? Discuss with detailed reference to Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. |

This question is drawing on the language of the module. The relevant key phrases from the module are:

To answer this question, you will need to address these aspects of the module.

One way of interpreting this statement is that:

Now we need to develop this into a thesis statement by combining these concepts into a couple of sentences that answer the question and discuss The Crucible. That could look like this:

“Storytelling allows composers to consider and criticise contemporary events for audiences by appropriating narratives from human history. Miller compels audiences to experience oppression through his dramatic interrogation of the growing tyranny of McCarthyism in the 1950s as he reimagines the historical narrative of the Salem Witch Trials.”

Once you’ve written an essay, you will need to edit it. In the next post, we’ll have a look at how to proof and edit your work in detail.

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.